November 17, 2019

GREG HARROLD

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

The Spanish Baroque Organ at Oberlin

November 17, 2019

GREG HARROLD

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

The Spanish Baroque Organ at Oberlin

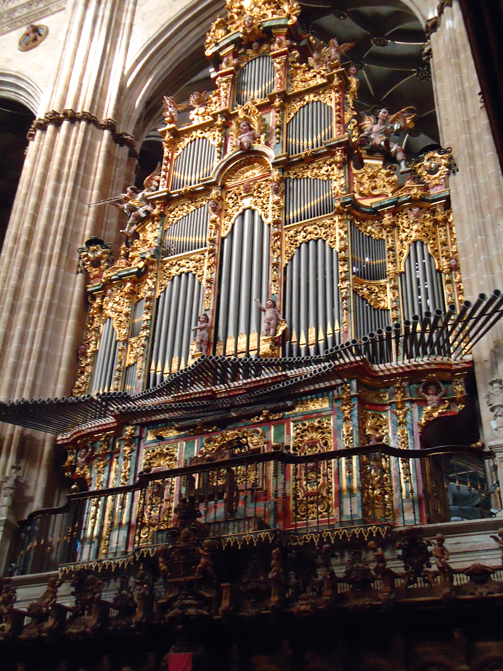

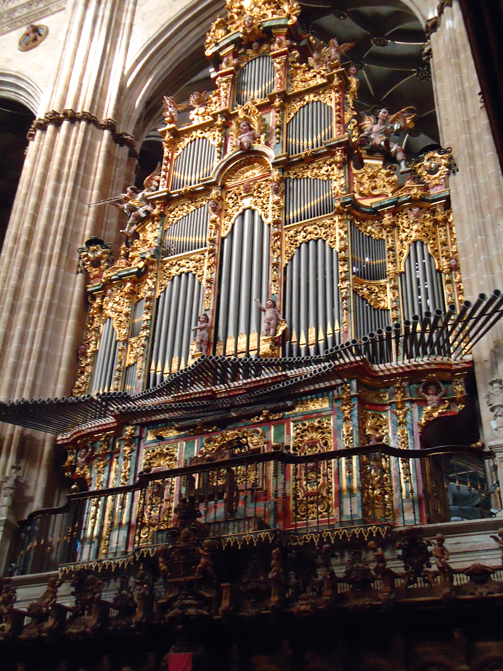

The 1989 Greg Harrold organ at Warner Concert Hall, Oberlin Conservatory, Ohio.

The 1989 Greg Harrold organ at Warner Concert Hall, Oberlin Conservatory, Ohio.

I travelled to Salamanca, Spain with Professor Lawrence Moe in 1984 to attend the Spanish organ music interpretation class taught by Guy Bovet and Montserrat Torrent. On the first day, the class of 20 were let into the enclosed choir in the center of the New Cathedral, where we sat in fancifully-carved ancient choir stalls. Above us to either side were the organs, each situated on a stone gallery between a pair of the main supporting piers. Each organ had two case fronts, one facing into the choir and another facing out. The larger organ, dating from 1744, was built by Pedro Echevarría; the smaller organ, which has casework from 1558 and was revised around 1700, is by an unknown builder.

Guy Bovet began to improvise on the 8’ Flautado of the older organ. We were transfixed. The sound was haunting and mystical, its gentle voice disappearing into the distances of the great building. He alternated it with the gentle, distant Flautado on the exterior façade, played them in consort, then built up to the full chorus, a sound which was not loud but silvery, transparent, and strangely melancholy. The single 4' stopped flute was sweet and colorful, the mounted Corneta strong. We were surprised to hear an echo to the Corneta. It became quieter and louder when the echo box lid was opened and closed. The effect was absolute magic! Both the reeds inside the case and the horizontal trumpets outside were raucous and free-sounding. Bells tied to the beards of two sculptured faces jingled when their jaws were snapped open by a pedal, bringing a smile to all of our faces.

There was a pause during which Mssr. Bovet walked to the opposite gallery to play the great eighteenth-century organ. The gentlest sound filled the cathedral, deep, sure, and elegant, from the 16’ Flautado de 26. Again, a chorus was registered, stop by stop, displaying the contrast between the two manuals. Finally, the brilliant Sobrezímbala was added to perfectly balance the gravity of the Flautado de 26. The clear, articulate stopped flutes were joined, rank by rank, by the hollow-sounding Nasardos. First the twelfth, then the fifteenth, seventeenth, and nineteenth. Left hand and right-hand solos showed the amazing blend and fluidity of these flutes. The pungent voice of the Corneta was accompanied by the rich 8' Flautado de 13, all on one divided manual — for me, the most Spanish of registrations. The beautiful 8' Trompeta Real was contrasted with the interior reeds of the second manual, Cadereta Interior. The shocking sound of the horizontal 8' Dulzayna gave us a start with its instant attack and crackling speech. Clang! Clang! The bells of the cathedral rang and were answered by a fanfare on the bold horizontal Trompetas. A distant echo came from the horizontal 8' Clarín on the exterior façade, sounding far, far away. The horizontal reeds on the interior façade blazed gloriously. Soon the entire, incredible reed battery was afire, making our blood race and spirits soar.

The experience of being in Salamanca — the big meal at noon, the siesta afterward to avoid the intense sun, afternoon coffee in the plaza, shopping during the paseo, the fabulous dinners at midnight followed by a brandy, the language, the climate, the food and the glorious architecture — put the Spanish organ builder's art in context.

Upon our return, Professor Moe suggested to me the idea of constructing an organ in the Spanish style for the University of California at Berkeley. There were none in the United States at the time, and he wanted an instrument different from those already in the university's collection, one that would be valuable for demonstrating a type of organ and literature largely unknown to American students. I was enthusiastic to create an organ that would share my excitement and love for these instruments. A second trip to Spain in the summer of 1985 provided an opportunity to gather more data.

Guy Bovet recommended that I focus on one regional type. We selected those organs built in the regions of Aragon and Castilla y Léon during the early eighteenth century. The characteristics of these organs are well suited to faithfully render most Spanish organ music. Two organs in particular provided most of the stylistic features on which I based my Opus 11. The first was the 1699 organ built by Josef de Manerú y Ximenez for the parish church in Longares. The second was the organ built in 1732 by Bartolomé Sánchez for the collegiate church in Cariñena. Other organs, such as those in Salamanca, Ciudad Rodrigo, Medina de Rioseco, Daroca and Zaragoza each contributed to my understanding and creativity.

When Professor Moe and I arrived in Cariñena, we retrieved the church keys from a sacristan at the parish house. The church was dark, but along each wall we could see fantastically-decorated wagons. There were maybe eight or ten, wildly festooned, and each with the effigy of a saint, all ready for a festival parade. We wondered if the procession had already taken place. At the far end of the church, high in a side gallery above the altar, was the organ. For two days we examined and played this wonderful instrument. It made a different impression on me than the Salamanca Cathedral organs, less elegant than the large one, more refined than the small one, with a sound distinctly its own.

Something will always be overlooked when an organ builder makes an instrument closely based on antiques. The questions a builder brings to such a project are important in this regard. There are many good answers to these questions, even though antiquity is certainly no guarantee of success. This is where the taste, skill, and artistic temperament of the builder makes its impact. There is a fragile balance between the absolute delight in working in an old style and the careful, balanced judgement needed for it to succeed.

It took me four years, working mostly alone, to build the organ. I designed everything about the organ, made the case, action, windchests, and the pipes. The exquisite carvings are the work of Dennis Rowland. He was able to capture perfectly the Spanish spirit. During the final stages of the project, Thomas Harmon fitted the reeds together, Alan Kay forged the iron stop action, and John Atwood and Jonathan Zimmerman worked on the bellows and bellows-pumping trestle. And, from the very start, Guy Bovet provided much valuable information and enthusiastic support. Professor Moe helped throughout the project with research, volunteered his time to leather the bellows, hand paint and gild the case, and assisted me during the voicing and finishing. His great interest in the Spanish organ and its music made this fascinating project possible.

There was not a suitable building on campus to house the organ, so it was loaned to Pacific Lutheran Theological Seminary, set in the beautiful wooded hills above the university. In 2017 the seminary sold its property and moved to downtown Berkeley, and therefore the organ had to find a new home. Once again, a suitable location for the organ could not be found, even after months of searching for a place on campus and around Berkeley.

Reluctantly, the Music Department decided to put the organ up for auction, and the Oberlin Conservatory of Music won the bid. In June 2017, David Kazimir, Patrick Fischer, and I disassembled the organ. The two of them drove the instrument, carefully packed in a truck, back to Ohio and put it in storage for a year. In August and September 2018, we reassembled the organ in its new home. It sits on a very solid, free-standing, raised platform at the back of the conservatory’s Warner Concert Hall. At the front of the concert hall, above the orchestra stage, is an organ built by Flentrop Orgelbouw in 1974. The warm acoustics are very flattering to organ sound. My Spanish organ has found an excellent second home 30 years after its completion.

Through careful study and comparison of the organs in Salamanca, Ciudad Rodrigo, Cariñena, Longares, and others, I derived an understanding of the guiding principles behind their design and construction. With this information I created an organ in a personal but what I believe to be an authentic style, albeit with some personal touches.

The manner of construction of Opus 11 is consistent with historic practice as much as possible. I wanted the organ to look, sound, and feel just like the instruments I studied. The fir case was hand painted dark and light blue, ivory and brick red, and gilded. Traditional wood joints were employed, and wooden pegs and square shank iron nails were used as needed. The façade is laid out like many of these organs, in five sections. The large pipes are in the center tower, the tenors in the side towers, and the trebles in the intermediary flats. The upper flats contain mute pipes. Moldings, carvings, paint, and gold leaf greatly enliven the flat case front.

The single manual keyboard has a short bass octave and is divided between middle c and c-sharp, which is typical of early Spanish organs. Contrasting registrations in the bass and treble are possible. They are called for frequently in the music of the period. The manual keys are hinged at the back. There are wooden rollers with forged iron arms. The wood trackers have wire tracker ends, which are bent over and hook into these arms and into eye wires in the keys. Action adjustments can be made by a slight crimp in the wire inside the pallet box. The pallet box and roller board are at the front of the organ, making the distance between the key and pallet short. The short pedal keys pull down the corresponding manual keys as well as operate an independent windchest for the pipes of the Contras de 26.

Forged iron stop action moves the wood sliders. By pulling just one draw knob the Corneta Magna and Corneta en Eco can be registered. A sliding pedal at floor level operates the mechanism that alternates the two.

The windchest was made with wood inlays plugging the top of the note channels and leather covering the bottom. There are leather pull-down seals and the pallets are glued in with a leather hinge. To my pleasure the reeds at both ends of the windchest speak very well.

The front pipes are disposed symmetrically but the windchest is chromatic. The conveyances to the front pipes are therefore complicated. Thick boards channeled and sealed with leather, along with metal conduits, take the wind from the windchest to the front pipes. Inside, the bass pipes also stand on channeled boards, and the Corneta gets its wind from metal tubes. In spite of all of this, the offset pipes speak promptly. The reed boots are made of a solid piece of wood, drilled and bushed with leather to receive the metal blocks.

There are two bellows of seven folds each, which can be raised manually by means of levers or the wind can be supplied by an electric blower. The bellows are not large, but because of the multiple folds they have great capacity. When first one bellows is filled then the next, the second one starts to fall with the first, evening out the pulses in the wind — yet the wind remains gently flexible.

The pipes have measurements like those of the organs I studied. The cutups of the flue pipes are moderate, and the windways are set at the optimum opening. Like the old pipes I studied, there is no nicking, and there is a counter-bevel on the front edge of the languid. I stayed as close as I could remember to the voicing techniques of these old pipes. The pipe metal alloy is close to that used by the organ builders I studied, 60% tin/40% lead for the flautado chorus and the reeds, 40% tin/60% lead for the flutes. The metal was hand scraped and was tapered in thickness on the large pipes.

The flautado plenum is based on the 8' Flautado Mayor de 13. The length of the largest pipe is stated in palmos, an old Spanish measurement which, in the region I based this organ on, is about seven-and-one-half inches. 13 palmos are equal to about eight feet.

When the Flautado is played alone each octave is distinctive. It is a register that can accompany itself by virtue of the timbral change from bass to treble. The triads in the bass octave, which occur frequently in Spanish music, are remarkably clear. The remaining stops add fullness and brilliance.

The flutes have both stopped and open pipes. The 8' Violón de 13 gets its name from its musical function, playing continuo. It has stopped pipes in the bass and chimneyed pipes in the treble. The sound is gentle and haunting. The 4' Tapadillo has chimneys throughout. The open flutes, Nasardos, sound at the twelfth, fifteenth and seventeenth. They almost equal the principals in loudness but have a much different character:

Domenico Zipoli: Pastorale, performed by Jonathan Moyer.

The Corneta Magna is mounted above the windchest, and the Corneta en Eco directly above it in a closed box. By means of a foot operated device these can be played in alternation for echo effects. One of the most beautiful divided-keyboard registrations in Spanish music is the Corneta Magna accompanied by the Flautado de 13. The dark, melancholy sound of the Flautado is illuminated by the power and color of the Corneta, a contrast of introversion and extroversion, darkness and light, grief and joy:

Guillaume-Gabriel Nivers: Suite 1 du premier ton, Écho, performed by Jonathan Moyer.

The reed pipes speak quickly with a distinctive attack. Inside the case is located the 8' Trompeta Real. It can be used alone, and it also blends well with the flue pipes. The horizontal reeds include a short-length 8' Dulzaina. It speaks with a peculiar and charming quack. The narrow scale of the left-hand 4' Bajoncillo imparts clarity. The right-hand 8' Clarín is almost identical to the Trompeta Real but the horizontal placement makes it seem louder. All of the reeds played together make quite a sound:

Juan Cabanilles: Tiento por A la mi re, performed by Jonathan Moyer.

Typical of the organs I studied, my Spanish organ is tuned in quarter-comma meantone and the pitch is a'=415 Hz.

To complete the organ there are some delightful sound effects. There is a Tambor (on D) and a Timbal (on A), each a pair of open wood pipes slightly out of tune to imitate drums, Cascabeles (bells) and the Pajaritos (birds, which you can hear toward the end of the first audio example above).

Disposition

| Spanish Flautado Mayor de 13 Octava Docena Quincena Lleno Címbala Violón de 13 Tapadillo Nasardo en 12a Nasardo en 15a Nasardo en 17a Corneta Magna Corneta en Eco Trompeta Real Bajoncillo Clarín Dulzaina Pedal. Eight notes: C, D, E, F, G, A, B-Flat, B Contras de 26 Effectos sonidos Tambor Timbal Pajaritos Cascabeles Tremblante Zapata para Cornetas Rodilleras |

English Principal 8' Octave 4' Twelfth 2 ⅔' Fifteenth 2' Mixture IV Cimbel III Chimney Flute 8' Chimney Flute 4' Open Flute 2 ⅔' Open Flute 2' Open Flute 1 ⅗' Cornet VII, treble, mounted Cornet V, treble, mounted in echo box Trumpet 8', interior Narrow Trumpet 4', bass, horizontal Trumpet 8', treble, horizontal Regal 8', horizontal Open Wood 16' Sonic effects Drum on Re, two pipes Drum on La, two pipes Birds Bells Tremulant Shoe to alternate the Cornetas Knee levers to engage Bajoncillo and Clarín |

––––––––––––––––––––––––

Editor's Notes

An earlier version of this essay was included in The Historical Organ in America, published by the Westfield Center for Historical Keyboard Studies in 1992, a collection of 12 essays by organbuilders, each describing an instrument that they built.

The Vox Humana Editorial Board offers our sincerest thanks to Jonathan Moyer for his kind permission to include the audio examples.

––––––––––––––––––––––––

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the position of Vox Humana.