October 14, 2018

KIMBERLY MARSHALL

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Medieval Organ Music

October 14, 2018

KIMBERLY MARSHALL

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Medieval Organ Music

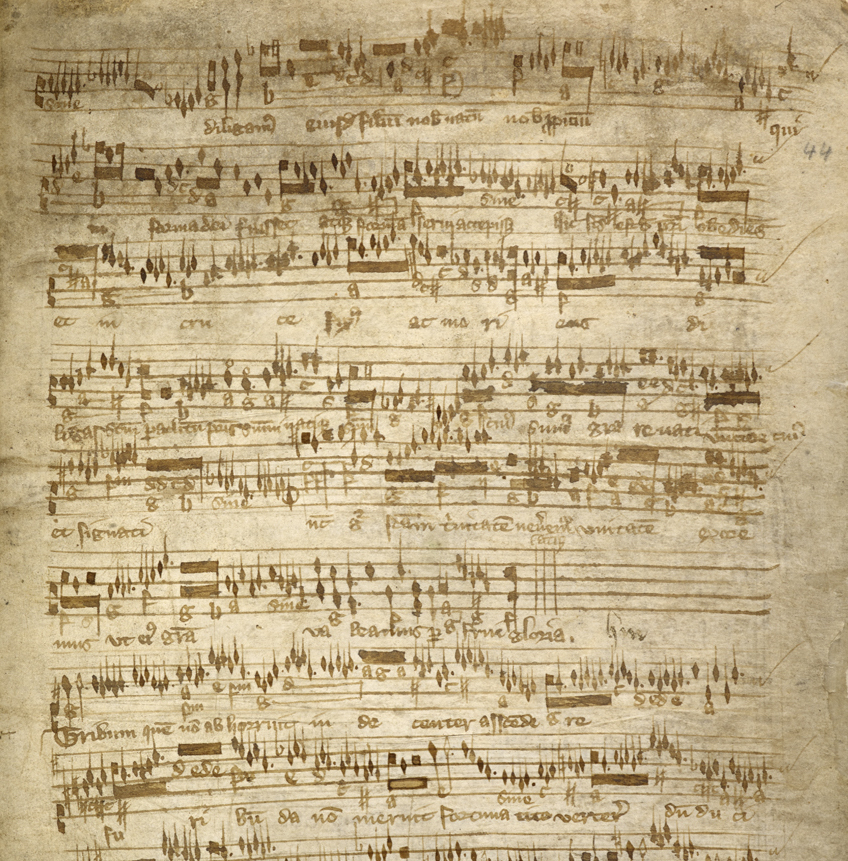

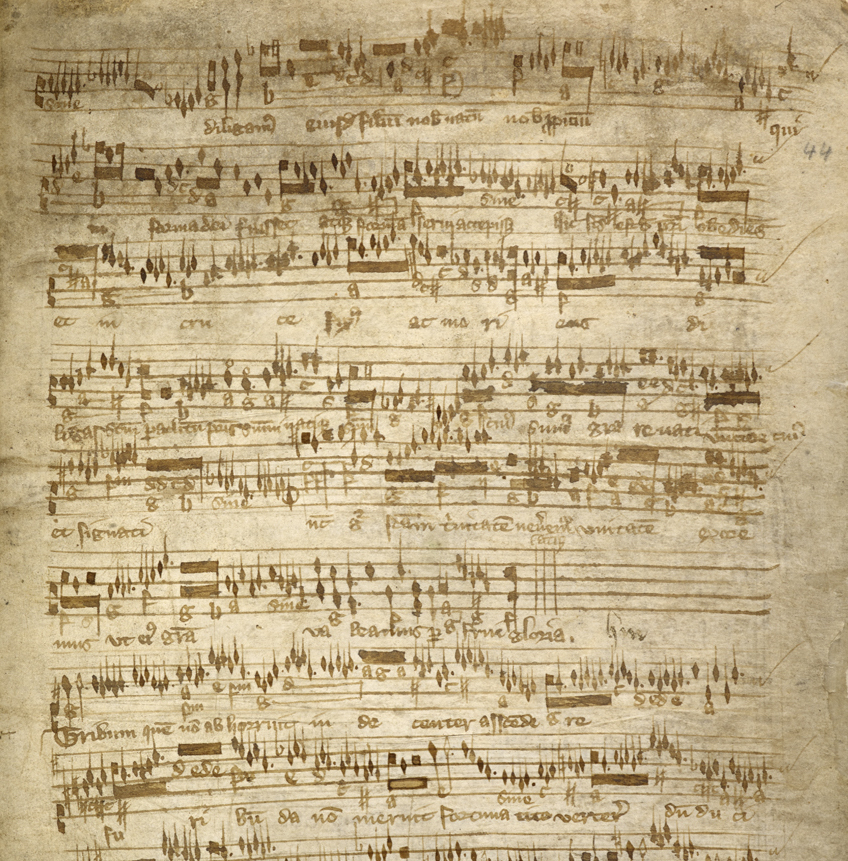

A page from Robertsbridge Codex, the earliest known pieces of keyboard music (c. 1360).

A page from Robertsbridge Codex, the earliest known pieces of keyboard music (c. 1360).

Introduction

Kimberly Marshall, Professor of Organ at Arizona State University, discusses medieval organ literature, instrument reconstructions, and ornamentation and improvisation practice with Vox Humana Associate Editor Guy Whatley.

––––––––––––––––––––––––

Professor Marshall, many thanks for agreeing to this interview. To begin, could you talk about your musical training? Did you study piano from an early age? When did you take up the organ, and what attracted you to it?

I was first drawn to the piano, not to the organ. My piano teacher in middle school was Margaret Mueller; her husband John Mueller was the organ professor at the North Carolina School for the Arts (now the University of NCSA). He came to one of my piano recitals and afterwards asked if I would like to study organ. He was a highly respected musician in my home town of Winston Salem, NC, so I felt obliged to say yes, but I also remember thinking “I really don’t want to play the organ! I want to focus on the piano.” Nevertheless, I thought I would give it a try, and I’m so glad that I did. John Mueller was a brilliant teacher, and he gave me access to the marvelous Flentrop organs at Salem College. (This was before the Fisk organ was built in Crawford Hall at the School of the Arts.) I also had a small Fisk practice organ almost to myself at the School of the Arts. It was a wonderful situation for study, and of course I got hooked on the organ because it is such an interesting instrument. I actually didn’t know much about organ playing before I started studying, and I think that’s true of a lot of my students. People often have a preconceived image of the organ, sometimes with negative associations, but that quickly changes once one starts learning about it and exploring the repertoire, especially if you have access to fine instruments, which I did. These were some of the earliest mechanical action organs in the United States. The Flentrop organ in Dr. Mueller’s studio was from 1958, the second Flentrop in the U.S. after the one at Harvard’s Busch-Reisinger Museum. Winston-Salem was the perfect place to be an organist because of these instruments and the Muellers, who worked together to foster an incredibly vibrant organ culture.

John Mueller was adamant that his students play the full repertoire, which at that time meant some pre-Bach (for example Buxtehude/Pachelbel and French classical repertoire), then Bach, Romantic, and Contemporary music. The Romantic was inclined towards French, although there were some in the studio who tackled the chorale fantasias of Reger. I was mainly interested in French Romantic literature at that time and played a lot of Franck. It is rather amusing now to think of myself playing Franck’s third chorale on that Flentop organ with the regal as the trompette/hautbois! Later I had the chance to play it on Cavaillé-Coll organs, so in a way, the Salem College Flentrop organ provided my training wheels. I was not at all interested in early music. Like most teenagers, I wanted to play big romantic pieces. I focused on the major nineteenth and twentieth century works, and I was a great Francophile so naturally I made the pilgrimage to France. I chose to study with Louis Robilliard in Lyon. He was (and still is) a leading interpreter of the symphonic repertoire, and he also improvised brilliantly in the symphonic style. He was an inspiring teacher, and I was fortunate to be his first American student. He made the Cavaillé-Coll organ at Saint François-de-Sales in Lyon available to me, the instrument that Widor’s father played. This instrument taught me a great deal about romantic music. I performed Franck and Widor, Liszt’s Ad nos and Messiaen’s Transports de joie on the Lyon Cavaillé-Coll.

I became interested in early music because of historical instruments. I had the opportunity to play some baroque organs during my time in France. I really loved their sounds, but I didn't have much music to play on them besides some Couperin and Grigny. I was thinking that I needed to explore the repertoire for which these beautiful instruments would be perfect vehicles. After finishing study in Lyon, I moved to Paris where I attended the weekend courses at Pierrefonds (about 100 km/62 miles northeast of Paris, near Compiègne) that were organized by Jean Saint-Arroman (musicologist) and Michel Chapuis (organist). Chapuis was a very natural musician; he could make anything sound fabulous with his marvelous touch and timing, and his ornaments were just gorgeous. I learned very much from the musicologist/performer team of Saint-Arroman and Chapuis, the best of both worlds. I remember going back to Lyon and playing the Grigny Tierce en taille for Robilliard. He thought it was rather good and commented that maybe there was something in this music after all. I was fortunate to continue my studies in France with Xavier Darasse, who helped me to hone my articulation and sense of style in the different baroque traditions. He was an inspiring musician and had an incredible joie de vivre which was contagious.

To summarize, what attracted me to early music was hearing historical instruments and wanting to discover how their sounds brought surviving repertoire to life. I was fortunate in being able to seek out experts in performance practice to mentor me in developing my interpretative approaches to early music.

How did you become interested in medieval organ music specifically?

After my time in France, I returned to North Carolina and completed my undergraduate degree, studying organ with Fenner Douglass. He had been giving me independent study credit during my time in France and was a perfect mentor for both the classical and romantic repertoire. He also encouraged me to pursue scholarly work to inform my playing, which led me to post-graduate study in England. As I explained, I had become interested in early music during my time in France; I also had the opportunity to study the Italian language and wanted to learn more about the performance of Italian baroque music. But for post-graduate work, I realized that I would need a clearly defined project that would justify living in England, so that I could write my dissertation in English. John Caldwell was renowned for his work in early British music, so I thought it would be inspiring to pursue my research under his guidance while also studying organ performance on my own with private teachers. In 1982, I was awarded a Marshall Scholarship (not my family’s foundation (!), but a scholarship funded by the British government in recognition of the Marshall Plan) to study in Oxford with John Caldwell; at the time I was planning to work on English baroque music. At Oxford at that time you began an Master of Philosophy degree program before switching to the DPhil (PhD), provided you could demonstrate that the scope of your research warranted a doctorate. As part of the MPhil, we had to prepare for an examination on the history of our instrument. So as part of my course, I studied the basic history of the organ. I came to the twelfth through fifteenth centuries and realized that there was something of a gap in our knowledge. We had sporadic treatises and iconography from the entire period, with musical sources starting in the mid-fourteenth century, but nothing was tying it all together.

At the same time I discovered that there was much organ iconography in manuscript sources, and as a great admirer of medieval illuminations, I tended to gravitate towards those. Another reason for my focus on medieval music was that I came into contact with Christopher Page, who was then a lecturer in English at New College, Oxford. It was an exciting time as he had just started his vocal ensemble, Gothic Voices. I remember going with a friend to a rehearsal at New College Chapel and hearing singers like Emma Kirkby, Margaret Philpot and Rogers Covey-Crump. They were experimenting with Pythagorean intonation, singing with pure fifths and wide dissonant thirds. It was just amazing. I thought I would benefit from working with Chris, the consummate scholar/performer, so I went to meet with him over tea (how English!) and we hit it off. He became my doctoral thesis advisor, later taking a position in music at Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge.

I originally became interested in medieval music from a scholarly perspective, later exploring the corresponding organ literature on my own. I took private organ lessons from experts who came through Oxford regularly, like Nicholas Kynaston and Gillian Weir, who was exceptionally encouraging. I also went to the Loosemore Center in Devon, where I first heard Jacques van Oortmerssen.

When did you start playing this music and how do you incorporate it into your concerts?

I didn't dare play too much medieval music in concerts early on, for fear that typical audiences weren’t ready for it. In my first teaching position at Stanford I presided over a large dual-temperament Fisk organ, so I was expected to perform mainstream baroque repertoire there. Nevertheless, I continued working on late-medieval organ music and developed ideas about performing it, culminating in the CD recording Gothic Pipes (available here), which included music from the three major collections of fourteenth and fifteenth century music. (This was recorded in 1993, but wasn’t released until 2004.) I tried to find ways to group the short pieces to create sets; for example, I played the double pedal preludia from the Ileborgh manuscript as intonations to some of the chansons from the Buxheim Organ Book. I then started using medieval preludes to enhance my recital programs. The pieces called “Redeuntes” in Buxheim are short intonation pieces based on drones with free figuration above, and these can serve as preludes for anything in the same mode or key.

Audiences have responded well — the drone gives a sense of musical gravitas characteristic of the Middle Ages. I’ve enjoyed performing the late-medieval repertoire in eclectic programs, including the one I presented as the opening recital for the American Guild of Organists Regional Convention in Salt Lake City last June.

I love finding ways to incorporate this music into concerts. You can't just play the pieces and say nothing to the audience — you have to figure out why this music is interesting and help the audience make associations with what they know. I often find that the audience feels that you are sharing something unique with them after you talk about the music. I remember doing a very large program with composers like Duruflé and Dupré, and someone came up and said that his favorite piece on the program was the Estampie retrové from the Robertsbridge Codex! I had prefaced the performance by suggesting that listening to one of these pieces is the closest that modern people can come to experiencing time as someone from the Middle Ages would. We can imitate the clothing, architecture and painting of the period, but when you experience time the same way as a person living in medieval Europe, that's really special. I want to stress that our earliest surviving organ music is great for concerts, teaching, and liturgical contexts. I attempt to show the ways this music can be used in the hope that other organists catch the bug!

It must have been exciting to be a pioneer in this field and bring music into the mainstream that was barely known, understood, or performed. Can you tell us more about bringing unknown repertoires to light? How has that changed now that this music is more in the mainstream?

The growth in interest in this music has been very gratifying to me; many of the developments in performance have been fairly recent. The Schola Cantorum Basiliensis in Switzerland has always been a center for early music and early keyboard study; also in Basel, the Edskes-Blank reconstruction of a fifteenth-century Hans Tugi organ in the 1980s was an important early step towards building an instrument allied to fifteenth century music (this is the organ I played for my recording, Gothic Pipes). There have been many subsequent efforts to build instruments based on late-medieval models, and creative music-making with this repertoire has been flourishing. I've just written an article for the British Institute of Organ Studies about all of this. The article celebrates Peter Williams's book, The Organ in Western Culture, which was published in 1993, 25 years ago, and describes the burgeoning interest in medieval organ music that has arisen since then.

Two years after Williams’ book appeared, a conference was held at the Abbey of Royaumont outside Paris. This was a gathering of scholars and performers who were studying medieval keyboard music. The conference featured a reconstruction of the twelfth century Theophilus organ by Antoine Massoni, and all the participants were able to try playing this instrument. The experience demonstrated to me for the first time that the sliders were light enough to permit very rapid playing. You could play drones by leaving the slider out (because there was no spring to pull it back in when the slider was released), and improvise florid figuration over these drones. A lot of people erroneously assume that the keys would be really cumbersome and difficult and that the music must be played slowly, in a ponderous way. Having a tangible feeling of the type of virtuosity possible was revelatory to me. Several musicians brought their own portative organs to Royaumont, creating a wonderful spirit of discovery. I was invited to give a paper about sources for improvisation and composition; I used the information in the fifteenth-century treatise De musica arte (Munich Stadtbibliothek MS 7755) to illustrate the patterns of late medieval keyboard music. Other influential musicians such as Marcel Pérès, Christophe Deslignes, Jankees Braaksma and Hans Fidom made important contributions. The proceedings of the Royaumont Conference were published in 2000 as Les Orgues Gothiques: Actes du Colloque de Royaumont 1995, edited by Marcel Pérès (Paris: Céraphis, 2000).

A revitalization of interest in medieval keyboard music occurred during the second decade of the twenty-first century. In 2012, there were multiple gatherings devoted to medieval organ music; David Rumsey documented some of them in his article, “In Search of the Secrets of Medieval Organs: the European Summer of 2012,” The Diapason (May 2013): 20–25 (available here). Rumsey commissioned master builder Winold van der Putten to make an organ in late-medieval style with constant scaling, based on iconographical sources such as the Pommersfelden and Rutland Psalters. Regardless of its length, each pipe has a diameter similar to that of a pigeon's egg (duivel ei in Dutch); this constant scaling produces very musical results for the late-medieval keyboard repertoire. The trebles are fluty and the basses are stringy, ideal for the sustained tenor cantus firmus lines supporting decorative melodies above. In 2012, the Orgelpark in Amsterdam inaugurated a modern reconstruction of the 1479 Blockwerk formerly in Utrecht’s Nicolaikerk, a stunning example of a new “medieval” organ. The following year, its annual three-day international symposium was devoted to this instrument, bringing together many leaders in the field of early keyboard performance, including a large number from the Royaumont Conference twenty years earlier. Koos van de Linde had presented a paper on the state of the original Nicolaikerk organ at Royaumont, and he had significant observations to make about aspects of the Orgelpark reconstruction.

So much related to late medieval musical performance is happening in Europe that I am sometimes frustrated to be so far away. But it was gratifying to hear that people have been using my old Oxford research on iconography to help bring this music to life by building modern replicas. The iconography has often been a starting point, but it cannot answer all the questions that arise when trying to make an instrument. One also needs to explore the surviving music for clues.

In The Organ in Western Culture, Peter Williams makes clear that even with all of the sources that he translates and interprets, there is simply not enough material to describe fully the reconstruction of a medieval organ. There are too many gaps that need to be filled in. And I would say that in the last 25 years, the focus has shifted from analyzing the documents to making music, using musical considerations help to fill in the documentary gaps. The end result has been collaborative, performers working with organ builders. A very good example is the player Martin Erhardt and the organ builder Marcus Stahl. Marcus said at first he didn’t want anything to do with "those screaming little things" (portatives). I laughed because that really is the way some modern portative organs can sound! But then he began working with Erhardt, who wanted a small organ to play with his medieval ensemble. He convinced Marcus to build it. They worked together on this organ and the result is spectacular:

It's very exciting to me that the emphasis is now on the music, which is where my interests are. It is thrilling that there are so many people working in the area and many beautiful instruments being built.

You wrote an article about the German treatise De musica arte, which describes the composition process and creation of late medieval organ music. And your recording Divine Euterpe opens with your own intabulation of the Agincourt Carole. You have gone beyond playing the music that survives in the small number of manuscripts from the period and have created your own. Please can you tell us about this?

I was creating a program themed around France and England so I thought the Agincourt Carole would be a perfect early link between the two countries. I also wanted to do something really dramatic to open the program so I intabulated the Carole in early fifteenth-century style, more or less the time of the eponymous Battle. Because this style locates the tune in very long note values in the left hand it's quite hard to hear, so I added refrains in my setting of the Agincourt Carol. I used the intabulation in my recording of music by female composers, Divine Euterpe, to illustrate the notion that “anonymous” is sometimes female.

I love the idea of making music in different early styles, and I want to encourage people to try creating their own “medieval” organ music. Improvisation is very important to this. There are places in the Buxheim Organ Book where the scribe didn't bother to write in all the voices of the composition. No. 239 of Buxheim, J’ay pris amours, is in three parts, but goes into two parts at times, making the voice leading somewhat erratic. David Fallows has suggested that the score is just a skeletal guide of what one should play. One shouldn’t hesitate to add a third voice in cadences, for example. It is important to bear in mind the ephemeral nature of the notation. I encourage players to be free with this music.

One freedom that I think is overdone, however, is adding ornamentation to late-medieval works. Modern organists often feel the need to add trills and mordants, almost as though they were playing French baroque music. Late-medieval repertoire is often highly ornamented, especially in treble passages. There might be contrasting places with less ornamentation, which I believe is intentional, to create contrast. So I’m loathe to make the simpler lines as replete with added notes as the florid lines, because this can destroy the balance of melodies in the music. Another problem as suggested above is that modern players tend to add ornaments from their experience of later music, such as seventeenth- and eighteenth-century trills and mordants. I prefer to look within the source to see if there is written-out ornamentation or figuration that I can adapt to other parts of the piece, rather than to superimpose another system of ornamentation onto medieval music.

I hope that organists will explore this repertoire, not constricted by the scant documentary evidence, but rather, inspired by it. When I began playing late-medieval repertoire, I found it liberating to know so little about it. Having played much organ music where the specificity of the notation and the technical difficulty left little to the interpreter, I found great freedom in interpreting medieval music, where I felt that I could do what I wanted as a musician. Not knowing much about its performance practice allowed me to make it my own. I experimented with registrations, tempi and articulations. Often organists have very strong opinions about aspects of Baroque and Romantic repertoire, even dividing into rival camps. When I started exploring medieval organ music, nobody really cared about it, and that took the pressure off!

There can be similarities between performing contemporary music and performing very early music; I believe that both can hone your creativity. What's interesting to me in the early literature is that the music is your only connection to its creator; with new music you can actually meet with and play for the composer, posing any question you wish. Yet it's really not that different because it can still be so hard to understand what a composer wants. When comparing Messiaen’s notation to his own performances or to the many different interpretations that he apparently endorsed, we realize that it's difficult to know exactly what he intended. Perhaps the notation isn't as precise as we imagine.

I want to encourage organists to try pairing new music with the medieval repertoire. The preambula in Buxheim are very strange and wonderful pieces, and I like to juxtapose them with contemporary music. You can even give the audience a quiz to see if they can tell which pieces are old or new!

Do you have any recommendations for organists who want to explore this music on their local instruments?

Organists can be challenged by the lack of access to interesting instruments on which to play this music; without beautiful sounds it's hard to make much sense of any repertoire. One of the most exciting developments in the U.S. is the construction of well-crafted instruments that enable organists to explore their creativity symbiotically with a fine organ. It doesn’t matter what style the organ is in, but it should have nice timbres. A balanced principal chorus and a couple of flutes go a long way towards realizing the late-medieval literature.

I was thinking about this issue when I published my anthology of late-medieval organ music (available here). Obviously I wanted to give a full gamut of the surviving fourteenth and fifteenth-century repertoire, but I also considered what would work on modern organs. And a lot of this music can work very well. I would recommend starting with some of the Robertsbridge Codex pieces and the Redeuntes (drone preludes) from the Buxheim Organ Book. All of this music has been published in scholarly editions, but if you don't have a good research library close by, you can always choose from my anthology, which contains many of my favorite pieces.

A big misconception is that everything was played on a Blockwerk, or a large principal chorus, and that simply was not the case. There were many small organs in the late Middle Ages; playing on a 2-foot or 4-foot principal or flute can imitate those. Pieces like those in the Robertsbridge Codex work very well on such registrations. Simply explore the resources of your organ. Don't imagine that everything has to be played on a loud, brilliant sound. Of course, sometimes it is fun to play this music on the full organ, recreating the large Blockwerk documented at Halberstadt Cathedral, for example. The Buxheim Redeuntes are very impressive played in this way.

When I started working with this music, I had no idea where it was going to lead... in fact, I still don't know where it's leading me! I've been studying the early repertoire for a long time now, and I always discover fresh new features in this fascinating music. There are many creative possibilities and a freedom of approach due to the lack of proscriptive rules. It's like discovering a garden of exotic plants. You can pick and choose which ones you’d like to cultivate or sit under. At different times of your life that's going to change — the garden is always there waiting for you.

When I was young there was an idea of what an organ recital should contain. There would be some pre-Bach like Buxtehude, a Bach work or two, a large Romantic work, and perhaps something modern. Much of the repertoire was known by the audience, or at least the style was familiar to them. Today, many audience members know nothing about the organ. Rather than lamenting this, we can seize the opportunity to introduce our audiences to whatever music we like and to how we are realizing it on the instrument. Instead of bemoaning the loss of knowledge among the general public, we can challenge ourselves to be advocates for the full repertoire of the organ. This allows us to program and explore whatever music we want, and that's been a very positive change that I've seen during my career.

Another aspect of concertizing that has changed for me is the need to speak to the audience, to explain connections or disparities between the pieces of the program, what to listen for, how the instrument is being used. When I started out as a concert artist, organists would just play their programs, bow and leave the stage. During my studies in England, I was very impressed by the eloquent way in which British musicians introduced their programs and interacted with the public. I had always wanted to share my musical ideas with audiences or to give them some background to the pieces that I was playing, and I learned a great deal from observing communication adepts like Christopher Page, Christopher Hogwood and Gillian Weir. At first I had to plan exactly what I would say and memorize it, but little by little it became more spontaneous and natural. Now, I usually include some verbal commentary in my concerts, depending on the venue and acoustic.

Organists must take their own journeys through our vast repertoire, and I hope that more will dive into the sea of medieval music (or at least dip a toe in from time to time). Playing this music links us with a centuries-old tradition and frees our creativity, encouraging us to be less pedantic and more inspiring as musicians.

What are your current research interests and projects?

I just performed and presented classes on medieval and Renaissance music in Göteborg, Sweden as part of the organ academy there. Göteborg is a treasure trove for organs, thanks to the advocacy and perseverance of Hans Davidsson, who spearheaded the construction in 2000 of an organ in Schnitger style, the largest existing organ in quarter-comma meantone temperament.

I always look forward to being back in Göteborg and to playing the fine instruments there, gaining knowledge and ideas from other organists as we recreate this repertoire together. I am especially grateful to be working with Koos van de Linde on teaching the early Dutch and German repertoires at the Göteborg academy.

I also hope to document the innovative work of three organbuilders who have made significant contributions to our understanding of various late-medieval organs: Winold van der Putten of Finsterwolde, the Netherlands, a pioneer in recreating medieval organs, including a number of portatives and several positive organs with constant-scaled pipe ranks; Marcus Stahl of Dresden, who has built some extraordinary portatives and regals, including the replica Chartres portative; and Walter Chinaglia of Cermenate (Como), Italy, who has made portatives inspired by paintings by van Eyck and Memling, as well as a positive organ based on a 1480 painting by Hugo van der Goes.

I am hoping to visit all three workshops and make videos that explore aspects of the instruments and how they render surviving repertoire, as well as how they inspire us to improvise. Hopefully, by disseminating the musical results of these European builders, we can stimulate an American renaissance of the Middle Ages!

––––––––––––––––––––––––

Marshall has performed throughout Europe, including concerts in London's Royal Festival Hall and St. Paul’s Cathedral; King's College, Cambridge; Norte-Dame Cathedral, Paris; and Chartres Cathedral. She has also performed on many historical organs, such as the Couperin organ in Paris and the Gothic organ in Sion, Switzerland. Her compact disc recordings feature music of the Italian and Spanish Renaissance, French Classical and Romantic periods, and works by J. S. Bach. Marshall’s expertise in medieval music is reflected in her recording, Gothic Pipes, as well as through her articles for the Grove Dictionary of Music and the Oxford Dictionary of the Middle Ages. To increase awareness of early repertoire, she has published anthologies of late-medieval and Renaissance organ music.

Kimberly Marshall is an experienced adjudicator, having served on the juries of the National American Guild of Organists competition (2008), the Sweelinck competition (Amsterdam, 2010) and the Alkmaar Schnitger competition (2015, the Netherlands). Locally, she serves on the Board for Rosie’s House, a pioneering music charity for children. She is the advisor on organs for the Musical Instrument Museum (MIM) in Phoenix and has made videos in Mexico, France, and Italy for their exhibits.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the position of Vox Humana.