March 10, 2019

NICHOLAS CAPOZZOLI

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

The French Classical Organ at Montréal

March 10, 2019

NICHOLAS CAPOZZOLI

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––

The French Classical Organ at Montréal

In no era of the organ’s vast history is an instrument so wedded to its music than that of the French Baroque. Whether it is the majesty of a Grand plein jeu or lyricism of a Tierce en taille, the versets of those countless livre d’orgues come to life on instruments from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Many composers have provided extremely detailed instructions of how their music should sound, and our ability to recreate such registrations today is an extraordinary gift. Unfortunately, organists in North America have few opportunities to play this music with timbres like those from de Grigny or Daquin’s time. While we play these pieces convincingly on French-inspired instruments or neo-Baroque ones of the Germanic persuasion, nothing compares to the fiery reeds, bold Cornets, and warm principals of a historic Clicquot organ.

Thanks to a generous donation and extraordinary vision, a close imitation does indeed reside in North America. Located in Montréal, Québec, a three-manual, 57-rank French Classical organ adorns the loft of McGill University’s Redpath Hall. The concept for this revolutionary and now historically-significant instrument came from former professors John Grew and Donald Mackey after an anonymous donation in the late 1970s. Grew and Mackey believed that such an instrument would enrich the pedagogical scope of the department, particularly in a city home to major Casavant and von Beckerath organs. They decided to hire the Swiss builder Hellmuth Wolff, who established his own firm in Laval, QC. While earlier attempts to emulate this style were made by Gilbert F. Adams and C.B. Fisk, Wolff’s opus 24 of 1981 would be the first of its kind: a twentieth-century North American reconstruction of an early French instrument. The disposition is as follows:

| Positif (I) Dessus de flûte 8’ Bourdon 8’ Prestant 4’ Nazard 2 2/3’ Quarte de nazard 2’ Tierce 1 3/5’ Larigot 1 1/3’ Fourniture III (1') Cymbale II (1/3’) Cromorne 8’ Grand Orgue (II) Bourdon 16’ Montre 8’ Bourdon 8’ Prestant 4’ Gross tierce 3 1/5’ Nazard 2 2/3’ Doublette 2’ Tierce 1 3/5’ *Fourniture III (2') Cymbale III (1/2’) Cornet V Voix humaine 8’ *Trompette 8’ Clairon 4’ |

Récit (III) Bourdon 8’ Prestant 4’ Cornet III Hautbois 8’ Pédale Bourdon 16’ Flûte 8’ Gros nazard 5 1/3’ Flute 4’ Grosse tierce 3 1/5’ Flute 2’ Bombarde 16’ Trompette 8’ Clairon 4’ Manuals I and II: 56 notes, C-g3 Manual III: 39 notes, f-d3 Couplers: Pos-GO, GO-Ped, Pos-Ped French or German pedalboard Tremblant fort*, Tremblant doux Rossignol Plein vent A=415 after d’Alembert * = half-drawn stop |

Before his project in Redpath Hall, Wolff’s knowledge of such instruments was (surprisingly) limited. He recalled: “The French organ was completely unknown to me. It was in the early 1960s, when I worked in Gloucester, Massachusetts that I heard the sound of a French organ for the first time through Melville Smith’s recordings of French Baroque organ music, as played on the Andreas Silbermann organ in Marmoutier, in Alsace.” Wolff later traveled abroad to examine Clicquot instruments, although the bulk of inspiration came from reading Dom Bédos de Celles’s L’art du facteur d’orgues (1766–1778). The master builder outlines every conceivable aspect of organ construction, providing thorough instructions, sketches, and measurements (most organists will probably recognize one such drawing at the end of the gallery below). By studying Bédos’s treatise, Wolff could replicate the exact dimensions of manuals, keys, and pallets, as well as pipe scalings and the shove coupler mechanism. In the design of the case, existing period instruments served as inspiration.

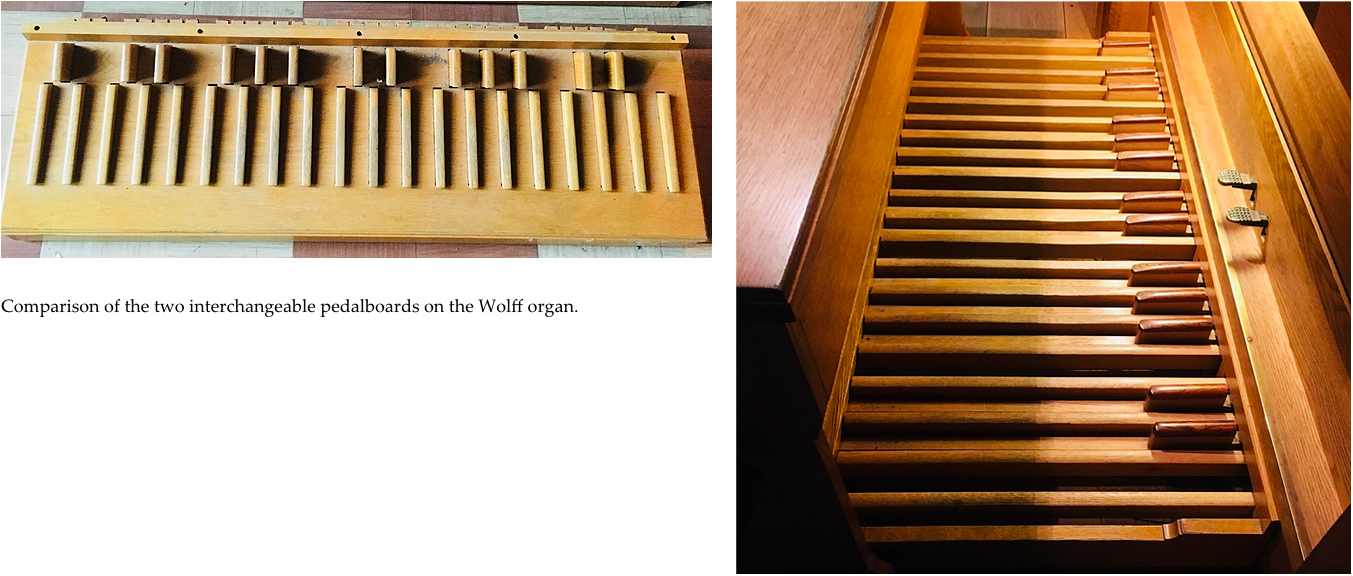

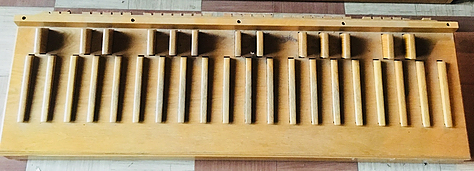

Despite his faithful rendering of dimensions and specification, Wolff made several compromises for modern convenience. He built two interchangeable pedalboards: one in the old French style with short keys and a more modern layout (see photos below). One will notice that the pedal’s compass extends to AA, playable only with the reeds. This change in spacing requires significant adjustment for the organist, although it does give him or her the rare opportunity to play that famous low B in the Gravement of Bach’s Pièce d’orgue, BWV 572! Additionally, Wolff offered two half-drawn stops for greater freedom in the literature. The player can open or close the lowest rank of the Grand Orgue’s Fourniture, allowing a 16’ harmonic in a Grand plein jeu and other polyphonic repertoire. One can also draw the 8’ Trompette of the same division halfway and play it only in the bass register. Pieces written for divided keyboard, such as Spanish Tiento de medio registro’s and some French Duos, are particularly effective with this feature.

The shape of the hall’s roof prevented Wolff from placing the pedal division within the central tower of the organ, a traditionally French practice. His solution of building it behind the main organ ultimately allowed for a larger pedal division than most period instruments. Finally, with an unequal temperament after D'Alembert, Wolff pitched the instrument at A=415Hz, not the French 392. These modifications are some of the builder’s many solutions that, while not entirely faithful to the French Classical aesthetic, offer students wider repertoire possibilities. One should also note that since its installation in 1981, the instrument has undergone important alterations in action, voicing, and the leather of the bellows. It is currently maintained by the Juget-Sinclair firm in Montréal.

The Redpath organ is in many ways a student’s greatest teacher. With its early French accent, one can experiment with the endless combinations of colours prescribed in the repertoire — everything from the hymns of Jean Titelouze to the galant music of Guillaume Lasceux. Beyond recreating those long lists of registrations, we learn how these sounds complement the music we play, as well as how they inform the way we play it. A survey of livre d’orgue prefaces of the period reveals a symbiotic relationship between genre, sound, and execution: one kind of piece calls for a specific timbre(s), which arouses an intended affect and thus should be played in a certain way. This exercise not only broadens our historical awareness, but also offers us new tools for musicmaking. For instance, a student sitting down at Wolff’s opus 24 with Guillaume-Gabriel Nivers's Veni Creator can now explain one movement’s curious title: “Couplet en récit de voix humaine, gravement: ou de cromhorne, plus légèrement.” The player’s choice of solo stop yields different expressive possibilities from both the instrument and music. Furthermore, the style in which one composes (or improvises) a Grand plein jeu versus Petit plein jeu is very different, and writers stipulate different approaches. André Raison argues for the slow and “legato” playing of a Grand plein jeu (plenum on the Grand Orgue), although one plays a Petit plein jeu (Positif plenum) “lightly and fluently.” Here is a demonstration of several historical registration combinations on the Redpath Hall organ:

Perhaps the most interesting registration exercise is the use of tremulants. While we commonly use the Tremblant doux (“soft tremulant”) with the Voix Humaine, several authors call for the Tremblant fort (“strong tremulant”) in a Grand jeu (reed and mutations chorus). This historical quirk actually makes sense in Redpath Hall, despite our modern skepticism of tremulants with full organ (for more on this, see Jonathan Young's article in Vox Humana here). From these few examples, we see that the art of registration is central to our understanding of French Baroque music and how to play it. Dom Bédos, the source of this organ’s inspiration, puts it succinctly: “The better an organist makes the organ sound, the more he is pleased, and the better he himself will play."

Wolff’s organ also offers the player invaluable lessons in touch. The unique speech of each stop requires careful control of articulation. In my experience, this is critical when using the Voix Humaine and Cromhorne, extremely articulate stops that call for an open legato rather than a complete detachée. However, playing a hymn of Nicolas de Grigny with the “old” pedalboard demonstrates the innate articulation in French pedal writing. The short keys do not allow a true legato, but only clear separation made possible with an all-toe technique. The relatively light touch of the manuals permits a graceful execution of ornaments, a feature found on period instruments (this also explains why composers could write embellishments in almost every measure of the literature!). Finally, the organ’s suspended action offers the player intimate contact with both the key and pallet. Controlling the speed at which a pallet opens or closes teaches one subtle finger tricks that maximize the vocal quality of certain stops and the sharp attack of others. Proper touch is most crucial when playing thick textures on full organ, for the player must release in a way that avoids an unwanted “hiccup” in the wind supply. Thankfully, Wolff has supplied a Plein vent to assist with such situations; one activates this feature by pulling the Tremblant fort knob halfway.

Since the Redpath organ’s installation in 1981, Hellmuth Wolff led a movement that has inspired generations of performers, scholars, and builders around the world. The organ has been showcased at several North American conventions and was recently the instrument upon which McGill’s organ department played the entire Livre d’orgue de Montréal in a marathon concert. As gleaned in the accompanying recordings, this organ also welcomes repertoire beyond early music. Composers Bengt Hambraeus, Bruce Mather, Brian Cherney, and Hans-Ola Ericsson have written new pieces specifically for this instrument. Moreover, Wolff’s reconstruction has inspired the building of more French Classical instruments in North America, such as those by Guilbault-Thérien and Gene Bedient. These modern reconstructions of old instruments have provoked new discoveries from builders, scholars, and performers alike. Thus, the organ that adorns the front of Redpath Hall is a testament to the historicist vision and pioneering spirit of its age. Early music enthusiasts and contemporary composers breathe new life into its lungs, while today’s university students receive unparalleled instruction from an instrument once foreign in North America.

––––––––––––––––––––––––

The Vox Humana Editorial Board extends our warmest thanks to the Marvin Duchow Music Library at McGill University for their kind permission to reproduce images and the early sketches of the Redpath Hall organ here.

––––––––––––––––––––––––

Historic Organs of the World is a new series of short articles on Vox Humana, in which members of the Editorial Board present a less-known organ of historical and cultural significance every month. Articles include information about the instrument's history, photographs, and specification, as well as descriptions of what it's like to actually play the organ — the key action, what the organ sounds like at the keydesk versus in the room, the acoustics, and more, complete with short recordings. Through these tools, Historic Organs of the World seeks to demonstrate how these organs influence the interpretation of repertoire, and raise awareness of the great instruments that have helped shape every aspect of organ art.

A native of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Nicholas Capozzoli has established himself as a solo organist, harpsichordist, and chamber musician with great distinction and versatility throughout North America. He holds a Master of Music in historical performance and Bachelor of Music in organ performance from the Oberlin Conservatory of Music, where he studied organ with James David Christie and harpsichord with Webb Wiggins. An avid collaborator with vocalists and instrumentalists, Capozzoli has accompanied Oberlin College’s Musical Union and Baroque Orchestra. In the spring of 2016, he was the musical director and harpsichordist for a student production of Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas. Currently based in Montréal, Capozzoli is a Doctor of Music candidate at McGill University in the studio of Hans-Ola Ericsson, and is Interim Director of Music at Christ Church Cathedral. For more information, please visit www.nicholascapozzoli.com.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the position of Vox Humana.